The Path to a Diagnosis

by James Bryant, DVM, Diplomate ACVS

Pilchuck Veterinary Hospital’s new Equine Performance Sports Medicine Institute marks the latest milestone in the hospital’s 50-year history. A dedicated facility on Pilchuck’s campus, the Institute is led by James Bryant, DVM, DACVS. Just like their human counterparts, equine athletes often require specialized, advanced diagnostics and therapies. The Institute’s goals are to provide an accurate and timely diagnosis of performance-limiting conditions, and to devise a custom treatment plan to allow for recovery of the injury and maintenance of soundness afterward. For more information visit pilchuckvet.com.

In this article and one to follow in the February issue, we track the progression of an equine patient case study from start to finish. Our patient is an 8-year-old Thoroughbred cross gelding used for hunter classes who came to Pilchuck Veterinary Hospital with acute lameness. This study will illustrate the lameness examination and demonstrate the different diagnostic tests that can be done to arrive at the diagnosis and treatment plan.

History

The horse has been in regular exercise for the last three years, including going to three to five shows a year at the 3-foot level. When he was purchased, there was concern regarding the LF (left forelimb) having an upright conformation in the pastern when compared to the RF (right forelimb). However, radiographs were normal at the time of purchase, and he was sound. He had been sound with no prior lameness reported. The patient developed an acute LF lameness two days prior to coming in to Pilchuck, after jumping.

Evaluation, Day 1

A musculoskeletal examination was conducted in which all limbs, the back and the neck were palpated. The only abnormality noted was an increase in fluid (effusion) of the LF fetlock joint. The gelding was negative to hoof tester application on the RF, LH (left hind limb) and RH (right hind limb); he was mildly reactive to hoof testers across the heel of the LF foot.

On a straight line, the horse was a grade 3/5 lame (i.e., he had a consistent head nod on the left front), and the lameness was worse when he circled to the right. Flexion examinations were performed on all the limbs. He was positive to flexion of the LF distal limb and was negative to all other flexions. We then proceeded to diagnostic nerve blocks. We tend to start at the bottom and work up:

1) A palmar digital nerve block (desensitizes the heel region of the foot) resulted in no change in the lameness.

2) An abaxial nerve block (desensitizes the entire foot, pastern and sometimes the very bottom of the back of the fetlock) again resulted in no change.

3) A low 4-point nerve block (desensitizes the fetlock region) resulted in the horse trotting sound on a straight line and circle.

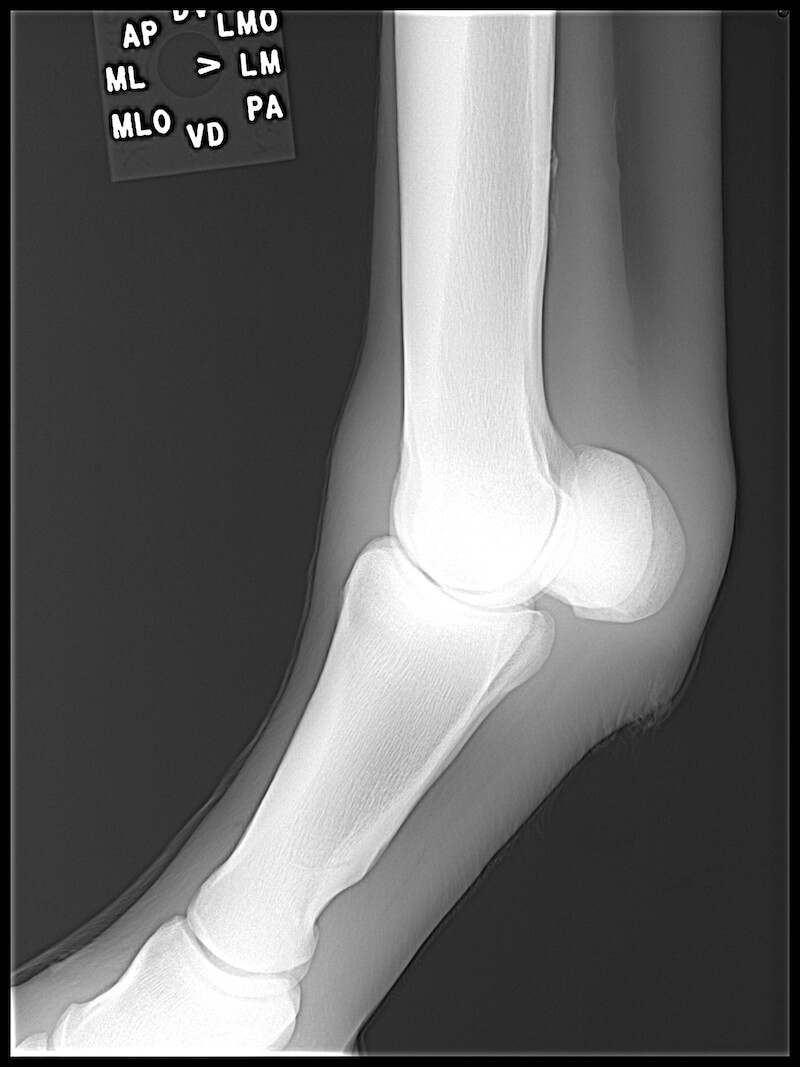

We then took radiographs of the left front fetlock; five views were obtained to give us a 360-degree evaluation of the region. No significant abnormalities were noted. After radiographs, a definitive diagnosis had not been reached; however, the location of the pain was identified.

Next Steps

At this point, there are several next steps that could be considered: 1) an ultrasound examination of the fetlock region, 2) diagnostic anesthesia of the fetlock joint, or 3) diagnostic and therapeutic treatment of the fetlock joint with local anti-inflammatories based on the presence of increased fluid. All of these options are appropriate, and horse owners should understand the importance of this in order to make an informed decision.

In this particular case, options 1 and 2 are very appropriate to gain more information regarding the diagnosis. With option 3, you are potentially treating the problem and may allow for the horse to improve clinically. However, if this option is chosen, be sure to consider the outcomes. These could include, the horse does not improve; the horse becomes sound for a short period of time (i.e., one to four weeks); or he becomes sound and stays sound without further issues.

Based upon the owner’s wishes for a definitive diagnosis before any treatment, the option of diagnostic anesthesia of the fetlock joint was chosen. With the limb having already been blocked on the initial examination and the horse currently sound (blocks with the drug mepivacaine [carbocaine] will last two to three hours), it was elected to continue the examination the next day.

Stay tuned: We will pick up at this point next month.

James Bryant, DVM, Diplomate ACVS, leads Pilchuck Veterinary Hospital’s Equine Performance Sports Medicine Institute and equine referral hospital. After receiving his veterinary degree from the University of California at Davis, College of Veterinary Medicine in 1995, Dr. Bryant completed an internship at Texas A&M University, followed by a surgical residency at the University of Florida.

Published January 2013 Issue

The Colorado Horse Source is an independently owned and operated print and online magazine for horse owners and enthusiasts of all breeds and disciplines in Colorado and surrounding area. Our contemporary editorial columns are predominantly written by experts in the region, covering the care, training, keeping and enjoyment of horses, with an eye to the specific concerns in our region.